Introduction

Definition and origin: Play to Earn (P2E ) refers to a category of blockchain-based computer games with their own game economies. It is characterized by players acquiring digital assets (e.g. tokens or NFTs) that have real value through gameplay. This concept emerged in the late 2010s within blockchain gaming. CryptoKitties (2017), a game in which digital cats were traded as non-fungible tokens (NFTs), became known early on. However, the model only gained greater attention in 2021 with titles such as Axie Infinity, which quickly attracted millions of players and generated high sales. P2E games promised a small revolution: players would no longer be mere consumers, but real owners of their virtual goods with the opportunity to earn money through gaming. In developing countries, this was even advertised as a new income – for example, some players in the Philippines were earning over 300 dollars a month with Axie Infinity at times, significantly more than the average local wage. For a lawyer well-versed in blockchain law, this raises the question of whether these economic promises stand up to a legal reality check.

Economic promises: The P2E model aroused enormous expectations. Proponents saw it as a paradigm shift that would give players a share in the financial success of games. “Play-to-earn blockchain games … could lead the way to a more equitable, opportunity-rich global economy”, enthused enthusiasts during the 2021 crypto boom. Players invest time (and often money for start-up capital such as game tokens NFTs) in the hope of making a profit by reselling the items or tokens they earn. Especially in low-income regions, P2E was seen as an opportunity: thousands of Filipinos, for example, jumped on the trend and some were initially able to improve their living conditions. At the same time, investors poured capital into P2E start-ups, sensing a new lucrative business model (keyword GameFi). A hype arose around virtual economies with trading volumes in the billions in some cases – Axie Infinity became the “most valuable NFT collection in the world” in 2021 with a trading volume of over 4 billion US dollars.

Disillusionment: In the meantime, however, disillusionment has set in. Many P2E games proved to be unsustainable; players stayed away or migrated, token prices and NFT prices collapsed. Axie Infinity, for example, lost over 90% of its market value and most of its users. Many who were hoping for high returns are now faced with empty wallets and disillusionment: “Fourteen months later, most Filipino players … have exited the game nursing anger and anxiety – and, in some cases, thousands of dollars down”. This development puts not only the business model but also the legal framework of P2E to the test. This article examines – in a factual and legally sound manner – how Play to Earn should be classified from the perspective of German law. Civil law issues (virtual goods, contracts), regulatory aspects (financial supervision, MiCAR), criminal and gambling law delimitations and international perspectives (USA, Dubai) are examined. The aim is to highlight the opportunities and risks for developers, start-ups and players and to assess whether P2E can be merely a temporary bubble or a sustainable model with a clean legal structure.

Technological basics of Play to Earn

In order for the legal classification to succeed, the basic technical concepts of Play to Earn must first be clarified. P2E games are inconceivable without blockchain technology and crypto assets. The most important elements are

- Blockchain as infrastructure: P2E games use distributed ledger networks(usually public blockchains such as Ethereum or sidechains) to document the ownership of game objects in a tamper-proof manner. Each item or token in the game is stored as a data record in the blockchain. This creates transparency and prevents the centralized manipulation of inventories – an advantage over traditional games, where all data is held by the operator.

- Tokens (fungible tokens): Almost all P2E games have at least one cryptocurrency(in-game token). These fungible tokens serve as in-game currency and rewards for achievements. Examples: Smooth Love Potion (SLP) in Axie Infinity or VIS in Pegaxy. Such tokens can be generated in unlimited quantities (typically as a reward for gameplay) and can often be exchanged for other currencies or fiat money on crypto exchanges. They therefore form the economic basis of the game world(tokenomics). Important: As soon as a token is freely tradable and has monetary value, it moves outside the context of pure gameplay and becomes the subject of regulation (more on this below).

- Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs): NFTs are unique, non-fungible tokens that typically represent game characters, virtual items or properties in the game. For example, the cute monsters in Axie Infinity are implemented as NFTs. NFTs give the player a technically securitized ownership right to the digital good: they can hold, sell or transfer the NFT in their own wallet without having to rely on the game operator’s permission. This creates real ownership of virtual items for the first time – in traditional games, the user contract only grants a right of use and the operator retains full control. However, the legal ownership classification of NFTs is complex, as although they are technically unique, they do not constitute physical objects in legal terms.

- Gaming ecosystem and marketplaces: Central to P2E is the existence of an ecosystem in which the acquired tokens and NFTs can be traded. Developers often operate their own marketplaces where players sell their NFTs to others (the operator earns from fees). However, many NFTs and tokens are also traded outside the game on general trading platforms (e.g. OpenSea for NFTs or Uniswap for tokens). This creates a secondary market where supply and demand determine the price of in-game goods. For such markets to function, the game must have a certain degree of decentralization – the assets must be freely transferable. This is a distinguishing feature from conventional games, in which item trading is often prohibited or technically prevented in order to avoid gray markets and legal problems.

These technological foundations lead to a fusion of the game and the real economy. Players’ virtual successes can be directly exploited economically (“in-game items with real-world value”). Legal advisors must therefore always keep an eye on both the IT-specific aspects (smart contracts, decentralized structures) and the financial market and media law implications.

Legal classification in Germany

Several areas of law are relevant for the legal assessment of Play to Earn in Germany. P2E games go beyond traditional categories, as they combine elements of digital services, financial products and games. In the following, the phenomenon is examined from the perspective of civil law, supervisory law, criminal law and gambling law.

Civil law: contracts, virtual goods and property

Contractual constructions: There are a variety of contractual relationships between the participants in a P2E ecosystem. Firstly, there is the user agreement between the player and the platform operator (game publisher), which is typically set out in general terms and conditions (GTC). These govern the conditions under which the player may use the game and what rights they acquire to the virtual goods. In classic online games, it is usually stipulated here that all items in the game remain the property of the operator and the player is only granted a limited right of use – an important instrument for maintaining control. With P2E, it could be argued that NFT technology should give the player a real right of ownership to the item. However, this is difficult from a legal perspective: under German law, only physical objects are property within the meaning of Section 90 of the German Civil Code (BGB). Virtual items or tokens are not property in the sense of property law due to their lack of physicality, but are considered data or rights. Consequently, NFTs and game tokens primarily establish positions under the law of obligations – i.e. contractual claims or licenses of the player against the operator. To a certain extent, the operator recognizes the game object embodied in the NFT and undertakes to enable the holder to use it in the game. As a rule, however, the operator does not grant ownership within the meaning of the German Civil Code (BGB).

Trading between players: Another contractual relationship arises when players trade game items or tokens with each other. For example, when player A sells an Axie NFT to player B. Legally, this constitutes a purchase agreement (Section 433 BGB) for a digital good. Even if the NFT is not a “thing”, the principles of sales law also apply accordingly to rights and objects of other kinds (Section 453 BGB). The seller therefore owes the transfer of the token (by signing the transaction on the blockchain), the buyer owes the payment (often in crypto). Nevertheless, such transactions differ from normal purchases: they are not technically carried out through traditional acts of fulfillment (transfer of an item), but through changes to the blockchain entries. Problems can arise where law and code diverge – for example in the event of bugs or hacking attacks. Who bears the risk if an NFT is “lost” due to a smart contract error? Such questions have hardly been clarified in case law and, in case of doubt, would have to be resolved via general rules (e.g. tort law, duty to maintain safety). It is conceivable that courts will draw analogies to the purchase of digital products in accordance with the contract.

Property-like rights to NFTs: Some legal experts discuss whether an NFT could at least be regarded as intellectual property. Similar to a patent or a share certificate, the NFT could be regarded as a special sui generis right. So far, however, there is no recognized legal basis for this. NFTs are neither legal tender nor traditional securities – they do not fall into any traditional ownership category. In practical terms, this is particularly relevant if a third party “takes away” an NFT without authorization (e.g. takes over the wallet through phishing). In the absence of a thing, there is no claim to the return of property under Section 985 BGB; the injured party must resort to tortious claims (theft of data, Section 303a StGB, or fraud) and claims under enrichment law. In short: from a legal perspective, virtual goods are data and are therefore only protected via contractual constructions. A well-drafted P2E contract should address this gap, e.g. by stipulating that NFTs are contractually assigned to the respective wallet holder and that the operator has no power of disposal without consent.

T&Cs and control mechanisms: The T&Cs of P2E providers are a key instrument for managing legal risks. For example, the operator can set rules for NFT trading (e.g. transaction fees, ban on off-exchange trades, exclusion of bot use, etc.). Operators often reserve the right to block accounts or freeze assets in the event of violations. However, decentralization in particular represents an innovation here: Can an operator “confiscate” an NFT? Technically not, as it is stored in the player’s wallet. But it could block further use of the game (the NFT becomes worthless because it is no longer accepted in the game). Such clauses must be carefully and transparently formulated in order to be effective (Sections 305 et seq. BGB). Particularly in view of the fact that considerable values are sometimes involved, it is important to ensure fairness and a balance of interests – an area that will probably increasingly occupy consumer lawyers and courts in the future.

Supervisory law: financial instruments, tokens and MiCAR

A key issue with P2E is the question of whether and when the tokens issued or marketplaces operated constitute financial instruments or financial services within the meaning of supervisory law. In Germany, the German Banking Act (KWG) is particularly relevant here, supplemented by European requirements such as the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) in the future.

Crypto tokens as financial instruments: Since the beginning of 2020, the German legislator has introduced the concept of crypto assets as financial instruments in Section 1 (11) KWG. A crypto asset is defined as a digital asset that is not issued by a central bank or public authority, has no legal currency status, but is accepted by persons as a means of exchange or payment or serves investment purposes and is electronically transferable, storable and tradable. This classically includes bitcoins and ether, but also game tokens, provided they are tradable beyond the game. Example: The SLP token from Axie Infinity was traded on exchanges and held by players as an investment – it therefore fulfills the criteria of a crypto asset (means of payment and investment function). As a financial instrument, crypto assets trigger various obligations: Anyone who trades, manages or holds them for others is operating a financial services business (e.g. crypto exchange or crypto custody business) and requires a BaFin license to do so. P2E platforms must therefore check whether their activities, e.g. as a multilateral trading system (marketplace for tokens/NFTs) or as an issuer of crypto tokens, require a license.

Classification according to KWG and WpIG: In addition to the catch-all category of crypto assets, gaming tokens may also fall under other categories – for example as units of account (Section 1 (11) sentence 1 no. 7 KWG) or as securities/securities. In most cases, however, the classic embodiment or the structure as an investment is missing. However, BaFin has made it clear that it applies broad standards: Anything that resembles a means of payment or investment and is traded on the market can qualify as a financial instrument. For example, even simple gaming points were considered units of account if they were freely convertible. This means for P2E tokens: As soon as players invest real money to buy tokens or tokens can be exchanged for money, financial market law comes into focus. A whitepaper or even a securities prospectus may then be required if there is a public offering component.

NFTs – utility or investment? The situation is somewhat different for NFTs. Individual NFTs (individual tokens) are not yet considered financial instruments by BaFin, provided they are unique and non-fungible. However, caution is required: “NFTs may be considered financial instruments”, which creates regulatory uncertainty. For example, if an NFT were linked to continuous revenue rights (e.g. profit sharing in the game), it could be considered a security or investment. Purely game-related NFTs (skins, items) are more likely to be classified as digital consumer goods – the contractual terms and conditions apply here rather than any special financial market law. Nevertheless, as soon as NFTs are traded on a large scale and used as objects of speculation, the supervisory authority will keep a close eye on this. In future, there could also be regulations for NFT platforms, e.g. in the form of transparency obligations.

MiCAR – European harmonization: The upcoming EU regulation Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCAR) will ensure uniform regulation of crypto assets in Europe from 2024/2025. MiCAR creates an EU-wide framework for crypto assets, their issuers and service providers. Essentially, MiCAR subjects all fungible tokens (except those that already qualify as financial instruments under MiFID) to certain rules. There are three categories: E-money tokens (stable value pegged to a fiat currency), asset-referenced tokens (stable by basket of values) and all other crypto-assets, including so-called utility tokens. A P2E game token such as SLP would be a classic utility token – it is used for access and utility within the game. MiCAR will require issuers of such tokens to publish a detailed information document (Crypto Asset Whitepaper) and file it with the regulator prior to the public offering. Unlike a securities prospectus, this does not have to be approved, but there are minimum content requirements and liability rules. For start-ups in the P2E sector, this means that issuing their own tokens to the public will be more formal and complex. However, MiCAR also creates legal certainty: what was previously a gray area is now subject to clear rules that apply throughout the EU. At the same time, crypto service providers (exchanges, custodians, advisors) will be subject to EU-wide authorization and supervision, which should increase consumer protection.

Transition and German supervisory law: National rules will continue to apply until MiCAR takes full effect (parts from June 2024, the majority from the end of 2024). In Germany, this means that even an NFT business that is actually license-free under MiCAR could be subject to BaFin supervision until then. Crypto trading platforms for games, for example, currently remain subject to the KWG. P2E developers should carefully check the licensing thresholds: Does the company operate a platform on which players exchange tokens with each other? Then it could be a trading system (Section 1 (1a) KWG). Does the provider store tokens/NFTs for the players (e.g. in a custodial wallet)? Then this is a crypto custody business (Section 1 (1a) sentence 2 no. 6 KWG) and has been subject to authorization since 2020. BaFin has made it clear that it is keeping a close eye on crypto assets – violations may not only result in the prohibition of operations, but also in criminal liability (Section 54 KWG). P2E start-ups are well advised to seek legal advice at an early stage and, if necessary, seek a BaFin license or a sandbox regulation instead of operating in a legal vacuum.

Criminal law: fraud, pyramid schemes and illegal gambling

The criminal law aspects of Play to Earn are twofold. On the one hand, it must be clarified whether fraudulent or pyramid game-like elements are present. Secondly, the question arises as to whether P2E could fall under illegal gambling if stakes and chance are involved.

Fraud risks and information obligations: Many P2E projects aggressively advertise chances of winning and high returns in order to attract new players (and their money). If these promises are objectively untrue or misleading, this could constitute fraud (Section 263 StGB). Fraud is committed when a financial loss is caused by deception about facts. This would be conceivable in the context of P2E: The operators deceive about the sustainability of the business model (e.g. promise secure profits, although the system only works with constant user growth). Players may pay a high entry fee (purchase of NFTs) that is never amortized – the money goes to former players or the operators. This is where the boundaries to a Ponzi scheme become blurred. Some critics openly refer to P2E as a pyramid scheme: “New players pay the profits of old players … Adele Spitzeder and Charles Ponzi send their regards.”. In fact, purely profit-driven P2E games are often zero-sum games in economic terms, in which only redistribution takes place without external added value. This becomes relevant under criminal law when a system is operated according to plan that only functions through a constant inflow of new funds and the initiators remain silent about the true risks. Germany’s criminal law does not have its own “snowball paragraph”, but such structures are sanctioned by fraud or prohibited pyramid schemes under the Unfair Competition Act.

Ponzi scheme vs. legitimate game: The demarcation criterion here is whether the game offers intrinsic added value (fun, entertainment) or whether participation is essentially only for the expectation of profit. If the game offers real fun and people could theoretically enjoy it even without the possibility of earning money, this speaks against a pure pyramid scheme. In this case, a lack of new players would have an impact on the economy, but the game would not collapse immediately as a core of players would remain for fun. However, if the entire model is geared towards new payers paying off the old ones, it is reasonable to conclude that it could be a fraudulent system. In this case, the prosecution must examine on a case-by-case basis whether there was any deception – for example about the prospects of success. A bad business model is not punishable per se, but if an impression of investment security was deliberately created (e.g. “the money works for you”), this can give rise to initial suspicion.

Unlawful gambling: Another criminal law dimension is criminal gambling law (Sections 284, 285 StGB). The legislator defines gambling in Section 3 GlüStV 2021 as a game in which a fee is charged for the chance of winning and the decision on winning and losing depends predominantly on chance. Classic P2E games are initially games of skill – the player has to fight, collect and trade. However, there are often random elements: e.g. the opening of loot boxes or the random generation of new NFTs (such as breeding in Axie Infinity, where the offspring have random properties). Section 284 StGB becomes relevant when players place bets in order to obtain a real chance of winning by chance. Some P2E models require the purchase of “loot boxes” or boosters that randomly contain NFTs of varying value. This is very similar in mechanism to a gambling machine (stake vs. random win). If such processes take place without official permission, the operator could be liable to prosecution for the unauthorized organization of a game of chance. The legal debate is controversial as to whether loot boxes in games are already games of chance. So far, German authorities have tended not to classify loot boxes as gambling within the meaning of the GlüStV as long as the prize is only of a virtual nature and no direct monetary value is paid out. With P2E, however, the virtual winnings have a monetary value (as they are tradable) – this increases the risk of being considered gambling.

Differentiation and eligibility: Not every P2E is automatically a game of chance. If the main influence on winning is the player’s performance (skill) and not chance, it is more of an e-sport or game of skill (not covered by the GlüStV). In addition, there is often no classic “stake”: many P2E games can technically be played for free, the investment in NFTs is voluntary in order to progress faster. In practice, however, initial purchases are often necessary in order to be able to play effectively – this can be considered a stake. Example: To start with Axie Infinity, you had to own three Axie NFTs, which at times cost a three-digit dollar amount. This purchase is functionally comparable to a wager to get a chance to win. If the game then contains random mechanisms (e.g. randomized battle results or breeding luck), it comes dangerously close to being a game of chance.

The legal consequences of illegal gambling are serious: the organizer is liable to prosecution under Section 284 StGB (up to 2 years imprisonment), participants under Section 285 StGB (up to 6 months). There is also the threat of regulatory measures – the Joint Gaming Authority (GGL) can have websites blocked and payments blocked. A P2E provider would have to obtain a German license for gambling, which became possible for the first time in 2021 for online poker and virtual slot machines. However, the requirements are strict (domicile in the EU, protection of minors, prevention of addiction, limitation of stakes, etc.) and it is questionable whether a P2E game could be forced into this corset. Conclusion on criminal law: Developers should design P2E mechanics in such a way that there is no illegal gambling – i.e. optional random reward design only without compulsory payment, or clearly positioned as a game of skill. Marketing and promises must also be honest so as not to constitute fraud. Otherwise, they are operating in highly risky legal territory with personal criminal liability for those responsible.

Assessment under gambling law (Section 3 GlüStV)

Gambling supervision law is closely linked to criminal law. In the Interstate Treaty on Gambling (GlüStV 2021), the federal states have regulated which games are permitted to be licensed. P2E models are new territory here and must be checked against the definition and system of the GlüStV.

Concept of gambling: As mentioned above, gambling occurs when a fee is paid in order to obtain a chance of winning and the prize depends on chance. Applied to P2E, this means: Does the game directly or indirectly require the use of money or valuable tokens for an uncertain chance of winning? A pure grinder, in which players earn tokens through diligence, would not be a game of chance, as there is no stake for a specific chance, but rather continuous performance. However, mechanisms such as loot boxes, gacha pulls or random NFT mints for a fee are critical. If, for example, players receive a surprise NFT for 10 tokens, the value of which depends on chance, the situation is very close to a game of chance (comparable to a lottery draw). In traditional games, it has been argued that the prize is “only” virtual. But as soon as the NFTs/tokens are tradable on the market, this profit represents a real thing of value – the distinction between virtual and real becomes blurred. There is therefore a real risk that P2E with such elements could constitute illegal online gambling in the opinion of the authorities.

Loot box comparison: Loot boxes in video games have been the subject of controversial international debate in the past. Countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands have already banned them as illegal gambling if purchased for real money. In Germany, there is (still) no explicit ban; the focus is more on protecting minors through higher USK/FSK ratings for loot box games. For P2E, however, it is clear that if a random-based reward is linked to a financial stake, you are at least in a gray area. In case of doubt, the GGL would require a permit – which does not exist for such novel mechanics, as licenses are only issued for defined offers (sports betting, online casino, slot machines). P2E does not fit into any existing category. The only option is therefore to avoid such chance-based pay-to-win elements or to design them without stakes.

GlüStV conformity check: A P2E provider must therefore analyze its game to determine whether the user receives a paid opportunity to participate in an outcome determined by chance. If this is the case, the game may be classified as a game of chance. Even if it is argued that the player has influence through their game performance (which partially relativizes gambling elements), a predominantly random factor is already sufficient. If it is unclear, the authorities could demand an expert opinion or temporarily prohibit the offer. Example: A game distributes NFTs as quest rewards, but which NFT (rare vs. common) you get is decided by lot. If players previously had to buy expensive equipment for this quest (with value), there is a stake/gain structure.

From the provider’s point of view, it is advisable to contact the gambling supervisory authority at an early stage and, if necessary, seek exemptions or – if the model allows it – an official license in a low-regulated EU country (Malta, Gibraltar) and rely on geoblocking in Germany. However, this would contradict the claim of a globally open game. Until the legislator creates clearer guidelines here, P2E models run a latent risk of being classified as illegal gambling and banned.

In summary, Germany is a difficult legal environment for play-to-earn: financial and gambling regulators tend to take a restrictive approach in order to ensure consumer protection, the protection of minors and financial market stability. Many P2E projects are therefore set up abroad; more on this in the next section.

International perspectives

The legal treatment of play-to-earn varies greatly depending on the jurisdiction. A comparison with the USA and Dubai (as part of the so-called Crypto Oasis) shows differences and can be decisive when choosing a location for P2E start-ups.

USA: SEC and Howey test – Are P2E tokens securities?

In the United States, crypto projects are primarily subject to securities law. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been examining many token models for several years to determine whether they are unregistered securities. The benchmark is the Supreme Court’s famous Howey test: an investment contract (and therefore a security) exists if (1) money is invested in (2) a common enterprise, (3) with an expectation of profit (4) substantially through the performance of others. The SEC has made it clear that it also applies these criteria to gaming tokens. In practice, the first two points are almost always affirmed – anyone who buys tokens or invests effort is making a commitment, and in the case of online games there is a joint project. Points 3 and 4 are controversial: does the player expect to make a profit from the hands of others? In many P2Es, this is exactly the case: players buy in-game currency/NFTs with the expectation of making a profit later on through an increase in value (which depends on the success of the game, i.e. the work of the developers). This means that the token often fulfills the Howey criteria and is considered an investment contract, i.e. a security.

The consequence: Offering unregistered securities is illegal, according to the SEC. Developers who sell in-game tokens or NFTs risk enforcement actions. The SEC can order injunctions, penalties and repayment of all investor funds. Back in 2018, the SEC warned that many utility tokens are in fact securities. Recently, it has increasingly taken action against crypto projects (e.g. SEC v. LBRY, SEC v. Ripple, etc.), although the classification has not always been clearly confirmed in court. For P2E, it is noteworthy that even if the primary use of a token is gambling, it can be considered security if the marketing or tokenomics imply promises of profit. Example: The developers advertise the token as an investment or retain a share to increase its value – this may be enough to fulfill the expectation for Howey.

However, there are also counterexamples: If a game token is distributed purely as an in-game currency, not publicly advertised for sale, and players only earn it by playing (and perhaps trading via third-party exchanges), it could be argued that there is no investment of money with the developer. Some crypto games in the US are trying to go this route: Tokens are not sold directly, but only gamed – the market is created secondarily. In this way, they want to avoid securities law. However, the SEC also looks closely at such cases, especially if the developers profit indirectly from trading or award initial tokens to certain groups.

Differences to Germany: In the USA, the regulatory approach in the crypto sector is principle-oriented and shaped by the courts (common law). The Howey test is flexible and can cover many things that could slip through in Germany due to a lack of legal definition. For example, in the USA there is no need for a specific list as in the KWG – investment contract is an open term. On the other hand, there is less discussion about gambling beyond the issue of securities, as this is dealt with separately at state level. A P2E game with gambling mechanics could possibly even be licensed in Las Vegas, whereas it would be completely illegal in Germany.

There are also differences in tax law: players’ profits would be taxable as income in the USA (regardless of whether there is a holding period), while in Germany private token sales could be tax-free after one year. However, given the complexity, we will leave tax issues aside here.

In summary, P2E developers in the US market must take particular care not to sell unregistered securities. Close coordination with U.S. attorneys and, if necessary, no-action letters from the SEC (a kind of clearance certificate) are advisable if you want to address American users. The risk of class action lawsuits from dissatisfied players (who see themselves as investors ) is also real – the U.S. legal culture is more prone to lawsuits for false promises or rule violations.

Dubai and the Crypto Oasis: Regulation in a sandbox paradise?

While Western countries tend to have strict to unclear regulations, the Dubai/United Arab Emirates region is aggressively courting crypto and blockchain companies. The buzzword Crypto Oasis stands for a flourishing ecosystem in Dubai, Abu Dhabi and the surrounding area that is attracting numerous start-ups. What makes Dubai attractive?

First of all, the tax climate: Dubai does not levy income tax or capital gains tax on crypto profits. Investors and players could therefore realize profits tax-free (although, for example, foreign investors are subject to their home country tax – US citizens are taxed globally). This tax advantage is part of the appeal, but is not the only point.

The regulatory approach is more decisive: Dubai created its own supervisory authority for virtual assets in 2022, the Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority (VARA). VARA issues rules and licenses to crypto companies in Dubai (outside the financial center DIFC, where the DFSA is responsible). The philosophy behind this is considered to be “progressive and responsive” with the aim of establishing Dubai as a global crypto hub. In fact, VARA offers clear regulations and seems to work more closely with the industry than many Western regulators. For example, Dubai has special free zones such as DMCC Crypto Centre or more recently RAK Digital Assets Oasis, which promise to allow crypto companies with simplified licenses. The latter even boasts of being the world’s first unregulated free zone for Web3 companies, although this does not mean that companies are allowed to operate there completely without regulation – they still have to comply with certain UAE standards.

Dubai offers the following advantages for play-to-earn start-ups:

- Licensing and sandbox: VARA has regulations on which activities must be licensed (e.g. exchange operations, custody, token issuance). Startups can obtain a provisional license comparatively quickly and test their model in a sandbox environment. The authorities seem willing to approve innovative models as long as basic consumer and AML requirements are met. For example, Crypto.com received a VARA license in 2023 to offer crypto services. A P2E game is likely to be classified – if at all – as a virtual asset service, which can be regulated in Dubai, while in Germany there may not be a suitable license category (or the effort involved is enormous).

- Clarity on AML/KYC: The UAE has issued clear regulations on the prevention of money laundering in the crypto sector. Companies must comply with strict KYC standards, submit SARs (Suspicious Activity Reports) and implement the FATF Travel Rule. This may sound strict, but it also provides a clear framework. Similar rules apply in Germany (GwG), but in Dubai the practical implementation seems to be easier for crypto companies in part because the authorities provide close support. However, AML is generally a challenge for P2E, where many micro-transactions take place – whether in Dubai or the EU.

- No gambling blockade: The UAE has traditionally had restrictive gambling laws (culturally), but the topic of video game lootboxes is less regulated there, as the focus is on crypto. A P2E game could potentially operate its mechanics as long as it is seen as “crypto-asset entertainment”. However, the UAE is also launching a regulatory push to regulate online gambling in 2023 – caution is advised here.

- Infrastructure and capital: Dubai offers access to well-funded investors and a growing community of blockchain developers. Many Asian P2E gaming companies have relocated to Dubai or Abu Dhabi to take advantage of the friendlier climate. Hundreds of companies are said to have relocated to the Emirates following the China crypto ban in 2021 (“blockchain startups in droves”).

However, there is also a downside: Market access to the EU/USA could suffer if you are exclusively regulated in Dubai – as European regulators do not accept Dubai licenses as a substitute for their requirements. Furthermore, the ongoing compliance costs in the UAE are not trivial (high license fees, local sponsor requirements, etc.). Nevertheless, Dubai is a serious alternative for the location choice of many P2E projects: you can operate in an internationally recognized framework, enjoy tax exemption and relative regulatory leniency as long as you do not commit any obvious violations.

Choice of location vs. Germany: A P2E startup that wants to set up in Germany faces complex legal issues, with uncertain chances of approval and potential prohibitions. In Dubai, on the other hand, it is welcomed with open arms as long as it registers and complies with certain standards. This dichotomy means that Germany often remains a bystander when it comes to new blockchain gaming trends, while innovation happens elsewhere. From a legal expert’s point of view, this should be honestly pointed out to clients: It may make more sense to initially set up operations abroad and later – once the model has been consolidated and, if applicable, regulations in the EU are clearer (keyword MiCAR) – to expand to Germany.

Economic and moral consideration

In addition to the strict legal analysis, it is worth taking a look at the economic realities and ethical implications of play-to-earn. Legal advice must take these aspects into account in order to protect clients from misconceptions. This is often the reason why traditional game developers are skeptical about P2E.

Unfulfilled promises and ROI errors: As already outlined in the introduction, P2E ultimately caused losses for many players. In the beginning, the promise of return on investment (ROI) was sometimes enormous – players were suddenly seen as investors. However, the system often only worked during the upswing phase. Early entrants were able to sell the NFTs they had acquired to later entrants at a profit and sell them to even later entrants and so on. As soon as user growth stagnated, the cycle broke: NFT prices fell rapidly, leaving the last buyers sitting on worthless “assets”. Take Axie Infinity, for example: an Axie cost a few dollars in 2020, up to USD 2,000 in 2021 during the hype, but the price plummeted in 2022. Many players had invested large sums (sometimes on credit), expecting steady returns, and then suffered massive losses. This late investor problem is similar to financial bubbles – this raises the moral question of the extent to which the operators bear responsibility. Did they provide transparent information about the risks? Or even actively nurtured the illusion that it was a case of playful money printing? Tilman Baumgärtel aptly wrote in the taz that Axie Infinity was “actually just a visual interface for generating a cryptocurrency” and allowed players from the global North in particular to profit from poverty in the South. This drastic description as digital feudalism puts a finger on the moral wound: many P2E games exploit the hopes of poor sections of the population, while the value creation ultimately ends up with a few profiteers.

Gamers as investors: The classic gamer plays for fun, spends money on entertainment. In P2E, they become investors who want to earn money. This changes the entire structure: Where previously frustration over a bad game was only emotional, it is now financial. Players make investment decisions (buying NFTs) and become speculators. Psychologically, this can have a toxic effect: In reports, formerly enthusiastic Axie players complain that the game has become a stressful chore to avoid losing money. The joy gave way to compulsion, similar to gambling addicts who want to recoup their losses. Legally, the question arises as to whether game manufacturers have a special duty of care towards such “investor players”. For example, do they have to issue risk warnings as they do for financial products? That would be new, but is being discussed. In any case, it is devastating for a provider’s reputation if players are financially ruined. A moral assessment therefore often leads to the conclusion that a pure play-to-earn, which only keeps players for the money, is problematic. The industry has also recognized this – there is an increased emphasis on the concept of play-and-earn, where the fun of the game should once again take centre stage.

Developers’ interests – Why do major studios shy away from P2E? The established game publishers (EA, Activision, Ubisoft, etc.) have so far only taken hesitant steps towards NFT/P2E. Ubisoft launched the Quartz program with NFT items for Ghost Recon in 2021, but received massive player backlash and soon stopped the project. Valve (operator of Steam) even went so far as to ban blockchain games from its platform completely, stating that it does not allow items with real-world value. The reason for this reluctance is complex:

Firstly, legal uncertainty – no major studio wants to take the risk of suddenly appearing as a financial service provider or gambling operator. Secondly, brand and reputation protection – the gaming community is currently reacting negatively to NFTs and “moneymaking” in games. Companies fear shitstorms and boycotts of their established franchises. Thirdly, economic cannibalization – traditional free-to-play models thrive on players continually pumping money into the game (for skins, loot boxes, etc.) with no chance of a payout. P2E would flip this model: Suddenly players want to extract money. This threatens the business model or requires completely new sources of income (e.g. higher initial sales, transaction fees). Many developers simply do not (yet) see a sustainable monetization plan that would be better with P2E than the previous system. There are also legal obligations: A studio that puts NFTs into circulation would have to worry about their long-term availability – what if the servers are shut down in 5 years? Could NFT owners sue because their asset becomes unusable in the game? Such questions are daunting.

Finally, ethical responsibility also plays a role. There is debate within the industry as to whether it is even desirable to entice players to “go to work in the game”. Critics speak of the risk of exploitation if, for example, wealthy players set up so-called scholar programs in which poor players grind for them (a phenomenon observed in Axie). This feels like colonialism 2.0 and clashes with the self-image of many developers who want to deliver entertainment and artistic vision, not just financial products.

Decentralization vs. platform control: Another aspect is control over virtual goods. P2E promises decentralization: players own their assets themselves and can trade them freely. However, this undermines the platform’s control over its own ecosystem. Traditional providers argue that they must be able to control the economy in the game in order to ensure balance and the gaming experience. If, for example, items are traded externally en masse, the black market and fraud can flourish – problems that were already known before blockchain (e.g. skin gambling with CS:GO skins). Blockchain makes the market more transparent, but no less real – now anyone can track the value of in-game items and, if necessary, trade them like stocks. For a development studio, this means that it loses some of its ability to design item flows because external prices and speculation play a role. The studio may also lose out on revenue: In a closed system, the operator earns from every item sale (e.g. loot box purchase). In an open system, players trade with each other, and if there are no royalty mechanisms in the smart contracts, the studio is left empty-handed. This is why many P2E games to date are from new companies that are experimenting while the big players wait and see or only try out symbolic NFTs (with no influence on gameplay).

In summary, it can be said that the lofty P2E promises have not yet been fulfilled economically – on the contrary, the fragility of the models has become apparent. Morally, P2E concepts have been criticized for turning fun into capitalist competition in which most people lose in the end. These findings are now also being incorporated into advice: a lawyer must point out to clients that a legally compliant P2E model not only has to overcome legal hurdles, but also fundamental economic doubts. Sustainability, fairness and transparency should be guiding principles if such a project is to be a success.

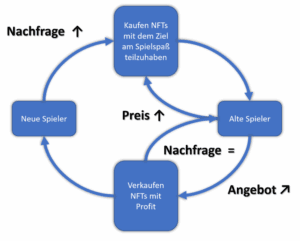

Diagram of a sustainable play-to-earn economy (upswing phase): The diagram illustrates the cycle in a P2E game. New players join and buy NFTs (e.g. game pieces) – this increases demand and the price of existing NFTs. The old players can sell their upgraded NFTs at a profit. As long as new players keep joining the game (demand ⬆️), the system remains balanced. Players therefore receive monetary incentives as well as fun. It becomes problematic when user growth slows down (demand ⬇️): If the newcomers stay away, there is no fresh money for the old players – the prices of the NFTs fall, many players leave in panic and the system collapses. A sustainable P2E model must therefore ensure that value is not only redistributed from new to old users, but that real value is created by the game (e.g. through external revenue or long-term motivation independent of the profit motive).

Legal risks for developers and start-ups

In view of the points outlined above, it is understandable that the legal risks associated with P2E are considerable. Developers and startup founders need to be aware of numerous pitfalls to avoid getting into costly legal disputes or regulatory action. The most important risk areas are:

Licensing and reporting obligations (BaFin, GwG)

A key risk lies in conducting financial market-related transactions without the necessary authorization. As explained above, P2E tokens and marketplaces can qualify as financial instruments or financial services. Providing such services without a BaFin license is illegal and can lead to business bans and even criminal proceedings (Section 54 KWG). Startups must therefore check at an early stage whether, for example, a license as a crypto custodian, proprietary trader (if they trade tokens themselves) or operator of a multilateral trading system is required. Applying for a license is time-consuming and costly, but there is often no alternative to being allowed to operate at all. One possible strategy is to design the business model in such a way that you remain below thresholds – for example, by not offering custody for customers (non-custodial wallet) or selling tokens to the community via third-party platforms. However, such constructions do not always help, and MiCAR will close many previous loopholes.

Money laundering obligations (GwG) also apply. As soon as a P2E provider is considered an obligated party (which is usually the case for crypto services), it must, among other things, identify customers (KYC), submit suspicious activity reports in the event of suspected money laundering and take internal security measures. Sections 10 and 11 of the AMLA in particular require the complete identification of users above certain transaction volumes and the reporting of unusual transactions to the FIU. In practice, this means that if players trade tokens for fiat or withdraw large sums of money from the game, their identity must be known and verified. This is a considerable hurdle for a global online game – anonymous crypto transactions are then no longer permitted. Some P2E platforms therefore limit payouts (e.g. only after KYC up to an amount of X per month). Please note: The AMLA obligations apply regardless of a BaFin license. Anyone operating without a license can also be a “person subject to anti-money laundering obligations”, for example as the operator of a trading platform for crypto assets. Violations of AMLA (e.g. no KYC, no money laundering officer) can be punished with fines in the millions.

Civil liability risks

Various liability issues arise in P2E projects: Is the operator liable if players suffer financial losses? Generally, providers try to exclude or limit their liability in their general terms and conditions – especially for lost profits or loss of value of tokens/NFTs. However, not every clause stands up to the scrutiny of T&Cs, especially in relation to consumers. For example, if an operator is grossly negligent in neglecting security and a hack occurs (as happened in 2022 with the Axie Ronin network, where over $600 million was stolen), it could be liable for damages if it is accused of organizational negligence. Players could argue that the provider had promised to keep the assets safe – this would be a breach of secondary contractual obligations.

System failures or the termination of the game also raise questions: If a game is discontinued, what happens to the invested values? In traditional games, virtual items end up worthless – the user accepts this as they have no ownership. In P2E with NFTs, the case is different: the NFTs continue to exist, but without the game they are de facto useless. Could players claim damages because the promised ecosystem disappeared? In this case, it would depend on whether the operator has contractually guaranteed continued provision. In most cases, general terms and conditions exclude this (“no claim to availability of the game”). However, such clauses could be invalid if the business model was implicitly designed for the long term. It would be uncharted legal territory, but it cannot be ruled out that courts would rule in favor of consumers in the event of a blatant decline in value, e.g. via frustrated business bases (Section 313 BGB).

Liability in player-to-player trading: Platform operators could also be involved in user-to-user transactions. For example, if a marketplace trade fails (e.g. NFT is not delivered due to a bug). This raises the question of whether the operator is liable as an intermediary. Terms and conditions often exclude any liability for user trades and the operator only sees itself as a technical service provider. Nevertheless, he could be held liable as an indirect tortfeasor if, for example, fraud is committed via his platform and he does not intervene. There is an analogy with auction platforms: On eBay, the operator had to intervene under certain circumstances to prevent infringements as soon as it had knowledge of them. In other words, if fraudulent offers appear on the P2E marketplace (phishing links, etc.), the operator must react, otherwise there is a risk of claims from injured users.

In addition, consumer protection rights must not be forgotten. For example, the right of withdrawal in distance selling transactions: If a user buys an NFT in the operator’s store, this is a digital product. According to Section 312f of the German Civil Code (BGB), the right of withdrawal for digital content lapses as soon as execution has begun, but the formalities (information, consumer consent to the lapse of the right of withdrawal) must be correct. If the provider fails to do this, a player could cancel the purchase of an NFT – which is problematic if the NFT has already been resold or consumed.

Finally, there is a latent risk of tortious liability: if the P2E game appeals to children or young people, for example, and they are deliberately tempted to play excessively due to the earning effect, it could be examined whether this constitutes immoral intentional damage (Section 826 BGB). This sounds theoretical, but the discussion about loot boxes and young players shows that moral and ethical boundaries play a role here. Companies should therefore incorporate mechanisms to protect minors (age verification, limits for under 18s).

Problematic contract design and GTC pitfalls

As mentioned, the terms and conditions and user agreements of a P2E game are the legal backbone of the offer. There are numerous traps lurking here:

- Ownership and usage rights clauses: It must be clearly regulated what exactly the player acquires when he buys an NFT. Do they only have the token or also a right to use the underlying character/image? What about copyrights (e.g. if a player creates or reuses NFT assets)? Unclear clauses could lead to disputes or invalidity. Ideally, the player should be granted a simple right to use the content for as long as they hold the NFT and define what they are (not) allowed to do with it.

- Fees and currencies: Many P2E games use their own tokens as currency. The terms and conditions should state that these have no fixed value, are subject to fluctuations and that there is no promise of conversion back into fiat (unless this is explicitly offered). Convertibility in particular is tricky: If the operator promises, for example, “You can cash out your tokens for real money at any time”, this could be considered a financial service (bureau de change) for regulatory purposes. It is better to state: “Tokens can be traded on third-party platforms; the operator itself does not exchange”. Transaction fees (e.g. % for NFT trading) must also be stated transparently, otherwise there is a risk of warnings for lack of transparency.

- GTC control: Consumer GTCs are subject to strict control in accordance with §§ 307 ff. BGB. Clauses that exclude liability for intent/criminality, for example, are invalid. The same applies to clauses that unilaterally give the operator extreme rights (e.g. the right to delete assets at any time without cause). Numerous judgments have already been handed down in this regard in classic games, e.g. on account suspensions. P2E providers should take care to specify important reasons for sanctions (cheating, payment fraud, hacking, etc.) and maintain proportionality. NFTs are a complex matter: if a user is banned, their NFT is worthless in the game – this is effectively an expropriation. Such consequences should be communicated openly and compensation should possibly be provided for (e.g. warning levels instead of an immediate ban).

- Choice of law and place of jurisdiction: P2E start-ups are often based abroad but serve German customers. The T&Cs then attempt to specify foreign law (e.g. Singapore law) and the place of jurisdiction is off-shore. However, this may be ineffective for consumers in the EU; they enjoy the mandatory level of protection of their home country and can sue at their place of residence. This means that even if the company is not in Germany, it could be sued under German law. Risk management should take this eventuality into account and not blindly rely on exotic legal clauses.

Further duties: Data protection, protection of minors, tax

Apart from the big issues, there are other legal obligations. Data protection (GDPR) is also relevant for P2E, especially when KYC is performed and financial transactions are tracked. An EU provider must be GDPR-compliant, e.g. provide information about data processing, obtain consent if necessary (e.g. if blockchain transaction IDs are published, which could be personal). Protection of minors: If the game contains elements that should be 18+ (e.g. gambling-like or monetary losses), it must not be made freely accessible to young people. In Germany, the state media authorities could classify a P2E game as “developmentally harmful” and require age verification. Start-ups should therefore consider a USK/PEGI rating and, in case of doubt, only offer the game from the age of 18 in order to be safe – but this limits the user base.

There are tax risks for both operators (VAT on commissions, income tax on winnings) and players (income tax on gaming revenue). The tax authorities may consider intensive P2E to be a commercial activity for players, with corresponding obligations to register a trade. There is a lot of potential here, but an in-depth analysis would go beyond the scope of this article. It is important to note that even if P2E operates in a legal gray area, it does not exempt companies or users from fulfilling their tax obligations.

Outlook: Future of Play to Earn – bubble or game changer?

After the boom and bust of the first generation of play-to-earn, the question arises: is the trend already over, or are we experiencing an evolution towards sustainable models? Some developments are foreseeable, both legally and economically.

Regulatory clarity on the rise: With MiCAR in Europe and clearer SEC requirements in the US, the legal framework will consolidate from 2024/25. On the one hand, this can increase the hurdles (because many P2E tokens have to be regulated), but on the other hand it can also create respectability. Projects that achieve compliance will be perceived as more trustworthy. BaFin-regulated or VARA-licensed games could be a seal of quality that convinces players that there is no fraud. Special license categories for play-and-earn may also emerge, e.g. in areas such as media or gambling law, if the pressure to contain such offers increases.

Shift to play-and-earn: According to the community and the industry, the future lies in play-and-earn rather than play-to-earn. This means that games should primarily be fun and retain a loyal community; the opportunity to earn money is an accessory, not the core purpose. Such games could have smaller, legal in-game economies (e.g. tradable cosmetic NFTs) without the full-blown financial incentive system that characterized early P2E. For lawyers, this means less risk, as virtual goods can be traded as before – just on the blockchain. One example trend is so-called soulbound tokens (non-tradable performance NFTs), which document successes but cannot be speculated on – something like this could replace reward systems without provoking legal problems such as securities status.

Integration into existing games: Perhaps we will see fewer purebred P2E games, but elements of it in major titles. Some studios are considering outsourcing parts of their in-game economy to blockchain (e.g. officially allowing item trading between players, but only with gameplay as the main element). Should such hybrid models come about, they will definitely be legally scrutinized and designed rather conservatively so as not to fall foul of any regulators.

New business models: One legally interesting concept is move-to-earn (players earn tokens for sporting activity) or learn-to-earn (educational games with token rewards). This blurs the boundaries with loyalty programs. Legally, such tokens could be considered reward points that can be redeemed for a limited period of time – similar to Payback, etc. Such models are usually uncritical as long as the token is not freely convertible. Perhaps one way forward is to design P2E tokens as a closed-loop currency (only usable in the game or with partners, no official secondary market). Although this reduces the attractiveness for pure “earners”, it could be legally simpler and still provide incentives.

Bubble burst, but…: Many experts consider the big P2E hype to be a bubble that burst in 2021. The user numbers and token market capitalizations prove them right. However, the idea of giving players real assets has struck a nerve. In a watered-down form – e.g. digital ownership of purchased skins – this is likely to remain. The trick will be to develop legally clean models that create value rather than just shifting it around. For example, future games could be ad-financed and distribute part of the revenue to the players as crypto (play and earn without new players having to pay). This would be sustainable as long as advertising money continues to flow – legally, on the other hand, clear contracts would be needed as to who gets how much, but not a Ponzi scheme. Cooperation with brands (NFTs as fan merchandise in the game) could also open up new legitimate sources of income for P2E.

Conclusion: Play to Earn is at a crossroads. It has disappointed as a short-term goldmine, but as an innovative concept it has left its mark. The challenge for a lawyer in the blockchain and gaming sector is to guide clients through this minefield – towards concepts that are both worth playing and legally compliant. The chances of this are better if lessons are learned from phase 1: Transparency towards players, compliance with regulation, building in safeguards against exploitation. If this succeeds, the former bubble could actually evolve into an evolutionary model that combines gaming and the real economy in a meaningful way. Otherwise, play-to-earn will remain a warning example of how quickly the mixture of hype, greed and legal uncertainty threatens to implode.

Sources: The explanations refer to a variety of sources from the gaming community, legal literature and official bodies. Selection (excerpt): Definition of P2E according to Chainlink; blockchain games Wikipedia; P2E market data and criticism (HackerNoon); Axie Infinity Case Study (taz, 2022); Ponzi analysis F5 Crypto; legal norms: Section 3 GlüStV 2021, KWG crypto value definition, BaFin leaflet; MiCAR classification (Bird&Bird); SEC/Howey application (Artaev Law); Dubai/VARA (CoinLedger) and many more. These and other references are cited in the text.