No products in the cart.

“Invested” in tokens and nothing happened? Get money back?

Currently, there are very many projects in the field of blockchain, tokens and coins and the potential "investment opportunities" are...

Read moreDetailsAlready a few times I have subliminally pointed out in blog posts the problem of what NFT actually are and what they are not.

NFT stands for “non-fungible tokens.” These are units that are unique and not interchangeable. Unlike fungible securities (e.g., stocks), where it does not matter which unit you own, each NFT is unique and cannot be exchanged. The first application for NFTs is Ethereum’s Cryptokitty series. These digital cats are a good example of “non-fungible tokens” as each is unique and not interchangeable. Each Cryptokitty has its own history, personality and equipment. Other applications for NFTs could include: digital artwork, digital property, or even digital health information.

Well, the honest answer (at least in Germany) is that we lawyers don’t really know yet. Lawyers and authors argue about the details, there is hardly any case law yet. In fact, many new legal questions arise in connection with NFT that call for innovative answers. Under civil law, NFTs could be considered “other rights” under Section 823 para. 1 of the German Civil Code (BGB), but – at least according to the overwhelming majority of opinions – they do not constitute absolute rights and, due to their lack of corporeality, they are not objects within the meaning of Sections 90 and 903 of the German Civil Code (BGB). The concrete legal significance of individual NFTs is therefore essentially left to the contractual arrangement by the parties. And this is exactly the problem I would like to address in this blog post.

For the legal relationship between the acquirer and the vendor of an NFT as well as for the rights associated with the NFT that relate to the reference object, it is therefore primarily a question of what absolute rights exist in the reference object under the respective legal system and what the parties agree with regard to the transfer of rights. In the context of the digital art market, which is particularly active at present, the absolute rights are primarily copyrights and the transferred rights are rights of use under copyright law, which are often also referred to as licenses or licensing rights.

From a copyright perspective, there are also a number of questions that need to be answered, e.g. how NFTs are to be classified in the catalog of types of use and which rights are transferred to the buyer with the sale of an NFT. Here, especially the creators of general terms and conditions are challenged to formulate the GTC correctly, which in my experience is currently rarely the case.

It is conceivable that the production and marketing of an NFT from a copyrighted work could constitute a (still) unknown right of communication to the public within the meaning of Section 15 para. 2 UrhG is a prerequisite. However, this classification is by no means compelling; it is just as conceivable that NFT have no copyright relevance at all, but that the (possibly property-like) ownership of the “digital original” is to be seen in isolation from any copyrights. In this respect, the buyer of a physical painting also acquires only the right to freely enjoy the work. That’s an idea that I personally, and I think many colleagues, can sympathize with. It does mean, however, that what the non-lawyer understands by NFT and what we lawyers understand by NFT would diverge. So, as I understand it, the NFT would be just a 3 KB memory that technically allows some kind of assignment of a right to the person who has access to the NFT, but legally is just nothing as long as the right embodied in it is not properly formulated or does not exist at all.

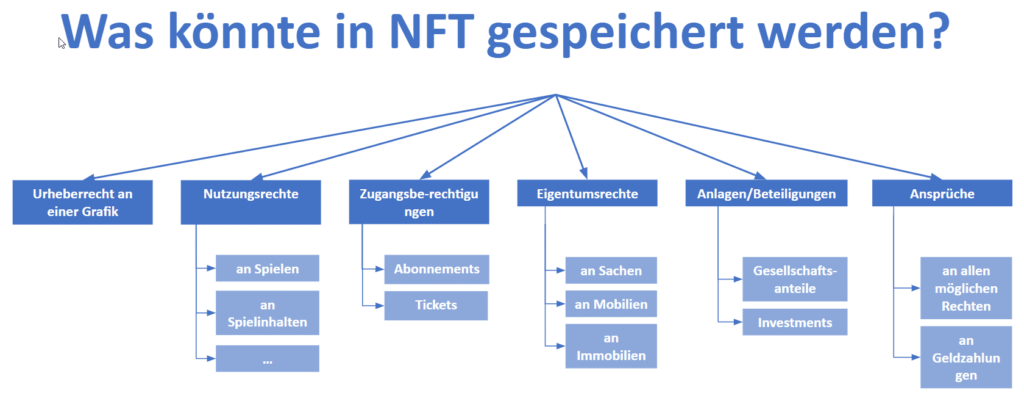

I think this is also denclogically correct, because even though NFT are often associated with pictures, monkeys or computer games, the token can actually do more, as you can see in the following graphic.

Bored Apes is a good keyword, by the way, because they are the reason for today’s blog post. In a court case in the USA, the issue is precisely whether the provider of the “Bored Apes” has registered the “copyrights” or whether he owns them at all. Even though the legal problem is very much focused on an aspect of U.S. copyright law, namely copyright registration, that European copyright law does not, it does give reason to think about the design of T&Cs and how NFTs are used. Because just because someone sells you a digital image in an NFT, that doesn’t mean you get the rights to the image transferred to you. It is not at all clear what you are allowed to do with the image, for example, whether you are allowed to print it on T-shirts and then sell the T-shirts or similar. All this can only be regulated by license agreements, which often contain an extensive catalog of rights. Buyers of NFT art often believe just the opposite.

The same applies to NFT in computer games, by the way. Just because you have received e.g. a virtual sword as NFT, it is – at least without knowledge of the GTC or the license agreement – not yet clarified what you are allowed to do with the NFT, e.g. whether you are allowed to use it in other games, whether you are allowed to “sell” it, etc.

Buyers of NFT should definitely pay attention to what they are buying and what rights they are buying. This is the only way to be sure about the possible value of the NFT. Sellers of NFT should take great care to have the T&Cs and license agreements reviewed by specialists in order to also be on the safe side and not have to put up with unnecessary frustration among buyers and bad PR later on.

Marian Härtel ist Rechtsanwalt und Fachanwalt für IT-Recht mit einer über 25-jährigen Erfahrung als Unternehmer und Berater in den Bereichen Games, E-Sport, Blockchain, SaaS und Künstliche Intelligenz. Seine Beratungsschwerpunkte umfassen neben dem IT-Recht insbesondere das Urheberrecht, Medienrecht sowie Wettbewerbsrecht. Er betreut schwerpunktmäßig Start-ups, Agenturen und Influencer, die er in strategischen Fragen, komplexen Vertragsangelegenheiten sowie bei Investitionsprojekten begleitet. Dabei zeichnet sich seine Beratung durch einen interdisziplinären Ansatz aus, der juristische Expertise und langjährige unternehmerische Erfahrung miteinander verbindet. Ziel seiner Tätigkeit ist stets, Mandanten praxisorientierte Lösungen anzubieten und rechtlich fundierte Unterstützung bei der Umsetzung innovativer Geschäftsmodelle zu gewährleisten.

Currently, there are very many projects in the field of blockchain, tokens and coins and the potential "investment opportunities" are...

Read moreDetailsIn line with my article from Tuesday regarding the VAT treatment of sales from app stores, there is information today...

Read moreDetailsIn today's digital world, blockchain, distributed ledger technology (DLT), gaming, and esports have become important and promising fields. Merging these...

Read moreDetailsCopyright for AI content: Current legal situation and open questions The nuuse of artificialartificial intelligence (AI) for thecreation of textstexts,...

Read moreDetailsIntroduction: In a recent conversation with a client, the topic of liability risks for managing directors of a limited liability...

Read moreDetailsThe FDP parliamentary group has tabled an entry to amend the Telemedia Act in response to the ECJ's cookie ruling:...

Read moreDetailsIn a decision from October last year, the Higher Regional Court of Cologne obliged the provider Cloudflare, which many website...

Read moreDetailsThe III Civil Senate of the Federal Court of Justice, which is responsible among other things for service contract law,...

Read moreDetailsCybergrooming is the targeted response of children on the Internet with the aim of initiating sexual contacts. Cybergrooming is a...

Read moreDetailsDefinition and legal basis: The European Cooperative Society, also known as Societas Cooperativa Europaea (SCE), is a supranational legal form...

Read moreDetailsIn this exciting episode of the itmedialaw podcast, we take a deep dive into the legal developments that will shape...

In this captivating episode, lawyer Marian Härtel takes listeners on an exciting journey through the dynamic world of influencers and...

In this personal and engaging episode, the experienced IT and media lawyer delves deep into the gray area of his...

Welcome to the third episode of our podcast "IT Media Law"! In this episode, we delve into the fascinating world...